|

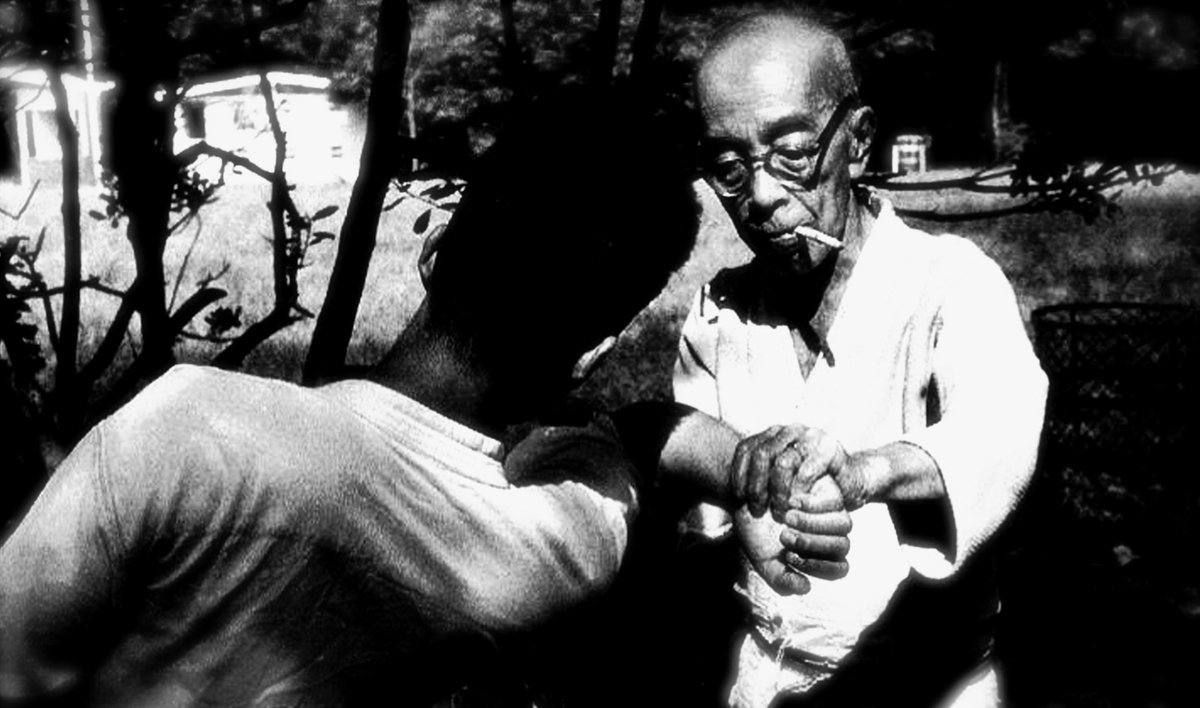

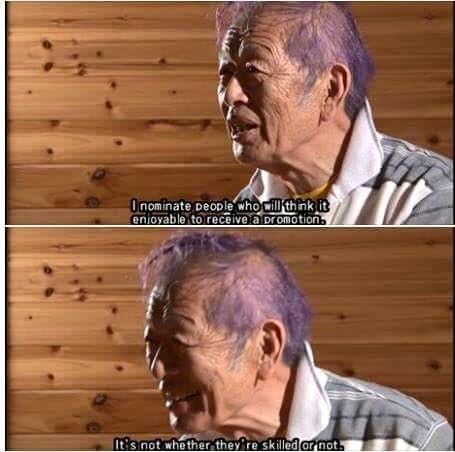

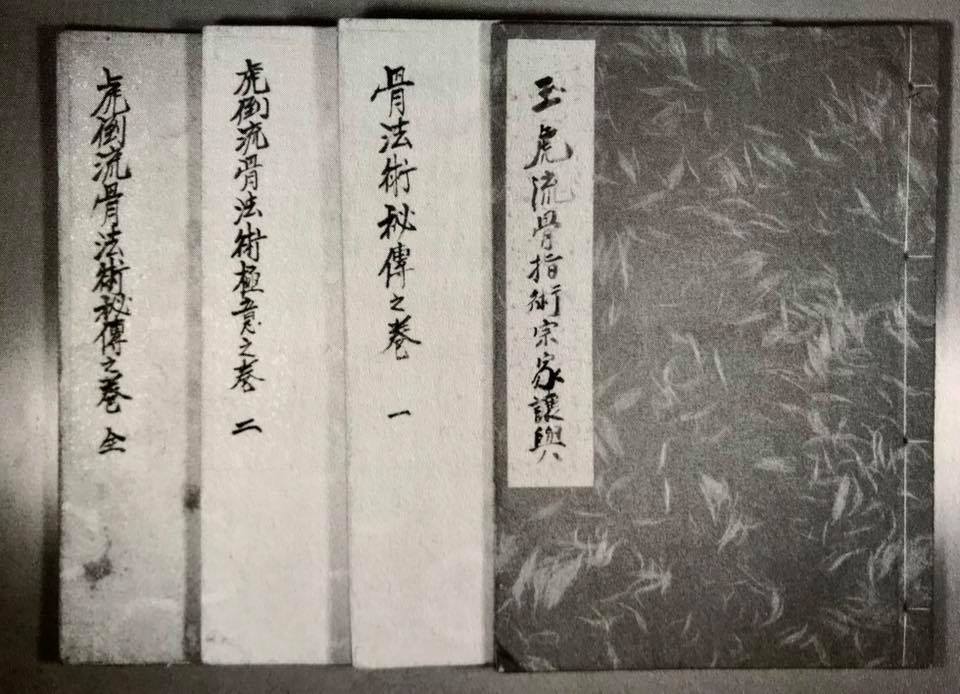

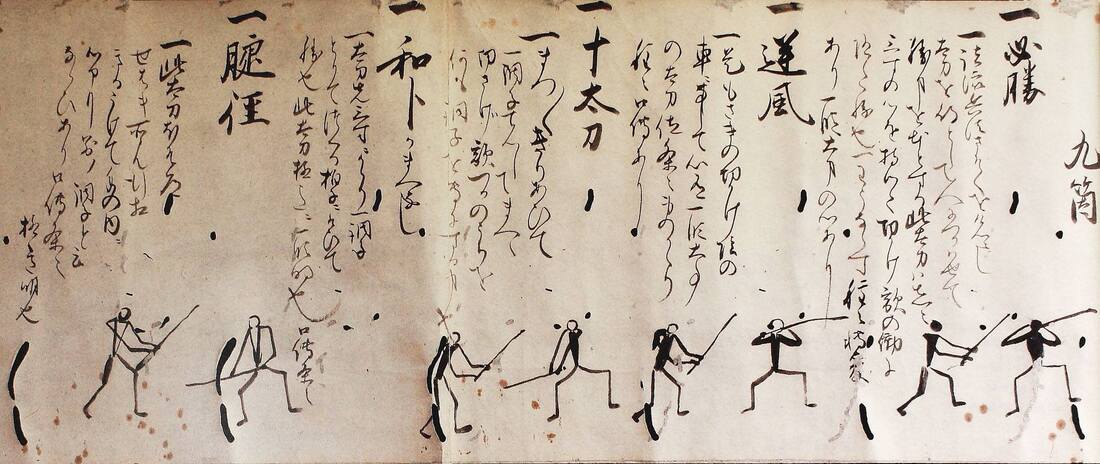

Editors note: This interview was conducted in April 2015, this is the full, never been published unabridged version of the interview I did with Dr Zoughari, its super long, any mistakes in it are my own as the Editor, and do not reflect on Dr Zoughari. Please enjoy, Gray Anderson. Hatsumi Masaaki, the Soke of the Bujinkan, is very unlike other Japanese heads of Budo, with his purple hair and the like. Would you say this is the case? How would you describe him as a researcher? Well this is an interesting question, honestly to tell you the truth I do not really care what the colour of his hair is or other things of this nature. The most important thing to remember is the “message in the bottle, not the bottle itself”, what I mean here is, how the man is, the way he lives the art, how he goes with, by, for and in the art, or how he carries the art and becomes one with it. I have met many Masters (Soke, Shihan) in classical Bujutsu, modern Budô and sports styles. All have great things to display, to sell, to show, to pretend. Some love to believe that they are the only one, the last one, The One….That their art is better; the most famous ryû-ha with the most prestige. I have talked directly and asked many questions to the Masters of many Ryû-ha, Masters who even told me directly that they never look at other arts or ryû-ha which I understand it to be, because they feel that it might corrupt the movement of their ryû-ha... Some even said that they should not copy the Master because if the master has bad habits, well the disciple will copy them too…. All of them are interesting to a point, all of them have something “to offer”, “share”, but after all, it is what you’ll do with everything you received from them and how far you’ll go, for what purpose…..so they are all special, each in their own way. The difference with Hatsumi sensei is clear: he will let you do what you want! Whether you are right or wrong, he will not judge you. This is quite hard for us westerners because we are used to being “lead”, to believe that the master is a teacher….in the classical Bujutsu and Heihô , the classical art of combat and war strategies and tactics, the master does not teach, he transmits. This means that the disciple is already a warrior, a grown man, not a child, there is no reason to tell him what he should do or choose, because if he cannot find it by himself, he will die during combat….In the time of feudal war, to transmit a science of combat, to find and choose the right disciple, was a very heavy task. Everything was based on a deep trust; in primary sources such as the Ichi Nin Ikkoku Inka (一人一国印可), written in 1565 by Kamizumi Ise No Kami, we find the phrase Seijitsu No Jin (誠実の仁), which shows the character, the disciple’s heart of nature, that it should be deeply honest and sincere, benevolent….so obviously finding a true disciple to show is not easy, especially when you are aware of the fact that all the classical Bujutsu as well as all the art and disciplines of Japan are based on the concept of ishin den shin (以心伝心) transmission from heart to heart, which goes beyond words, it means that everything is direct and that there is no need for words. Both, the master and the disciple understand each other, the two hearts are in sync. This is how Takamatsu Sôke formed his relationship and transmitted the Arts to Hatsumi Sôke. If you start to judge someone on his appearance or from an aesthetic aspect, the way he is, you judge from what you think you know according to your own value system and morals, and you cannot see beyond them. For a master like Hatsumi Sensei, this is a very good test in order to know someone’s heart and intention. Like many masters with their art and ryû-ha, Hatsumi sensei is the complete reflection of the essence of Ninjutsu, the reflection of the nine ryû-ha that he received from Takamatsu sensei. The way he is, represents the deep expression of a essence which is about no form, no trace, no intention, complete and deep, always in flow, between weakness and strength, flexibility and force, light and shadow, but always in the shadow of the art’s heart…it is very difficult to measure someone who, gives without wanting anything in return, who is and must stay the example to reach, to copy, and never let go, always on the top at even 84 years old, always taking the class, always flexible, always with a light smile and still enjoys the art and keeps a deep respect for his Master Takamatsu sensei. He gives to people what they want because he knows how the Shugyô , the deep and constant practice of this art is not easy, it is not for everyone, he knows the difficulty and understands more than anyone the weight of the transmission as well as the legacy. This is the reason why, he is light and open to everyone, whatever the style, the man, the religion, the country, the language, and most importantly in his capacity to say ‘’I do not know…..” His incredible interest in any art, any ryû, whatever the style, this openness, to study everything and not be limited or to stop at any level, vision, state of mind… In this case as you can see the purple hair is just a colour….I prefer to see the heart of the man, long term and I have not been disappointed once, and be sure that as a scholar I know how to stay neutral, in this case I do not play the slave or the “yes-yes student”, I speak my mind freely and according to my heart, this is the reason why I have learned Japanese too. Here in the few lines above, I have tried to give you some information about the history and the master/disciple relationship based on a science of combat born between life and death, because Ninjutsu is about that, among everything that deals with information, spying, etc. Because if you are not aware of the history, the context and facts that makes classical Bujutsu, Heihô’s history, describing Hatsumi sensei is simply impossible! After all, the man is complicatedly simple. Too simple and too normal that it is too complicated to understand, because we try to understand a man that no one knows or can even measure…because no one has the background and the experience of the practice in the art as well as the same devotion. Under Hatsumi Sensei, who is your teacher, and how does his approach differ to the Grandmaster and other Bujinkan seniors?My teacher is right now the oldest student of Hatsumi sensei (after 4 students, Mr Fukumoto (died), Mr Yonekawa (quit in the early days) Mr Manaka (creator of the Jinenkan) Mr Tanemura (creator of the Genbukan). His name is Tetsuji Ishizuka, he is well known by everyone, even the ones who badmouth him. No one has such a close relationship with Hatsumi Sôke like Ishizuka Shihan does, no one shares the same history with Hatsumi Sensei, with the creation of the Bujinkan, as he does! Most of the westerners use to come to his dôjô, he use to translate for Hatsumi Sôke a long time ago. He was involved in everything until he had to step back from the organization in order to support his family and because he had a very important job, he was the Deputy Chief of the Fire Department of Noda in charge of the entire budget of all the fire department of the Chiba prefecture, he had to deal with SAMU, Police and the city hall, he had a very important job and had to be in the field and station constantly, and every night kept his dojo, by running his class. I have witnessed this since 1989. Ishizuka Shihan started at Hatsumi sensei’s dojo when he was 16 years old. He was from Noda and he has never left Hatsumi Sensei and has always stayed by his side. Like I said most of the people, Japanese and westerners who badmouth him, know the true relationship between him and Hatsumi Sôke as well as his high class technique and skills. He is the Senior of all the other Shihan such as Seno, Noguchi, Nagato, Someya, Shiraishi, etc… He sticks to what Hatsumi Sôke taught him at the beginning, the densho, the Art, no compromise, no ranks for nothing, no trading the art, no prostituting the art, no teaching to earn a living or for the money, no lies. With him its practice and practice, study and study, and respect the art and each technique, no self-promotion or self-development. He is not after the money, he does not teach for the money, his job has provided him with a pretty comfortable life now. He has a passion for Hawaiian music, and is a singer and a bass player of Hawaiian music in a band that plays all over Tokyo professionally now that he has retired from the Fire department after 30 years. He practices the Art because he loves martial arts, he teaches because he believes and has a strong ethic and duty toward Hatsumi sensei, the art and the nine ryû-ha in the way Hatsumi Sôke taught him since the beginning. He received the Menkyo Kaiden (full transmission) in the nine ryû-ha. This year marks his 50th year of training with Hatsumi Soke! His approach is simple: he does not lie to you, nor does he do it for the money, he does not care about the number of the people who come to practice or not, he is the same, always smiling, always laughing, and is the most sincere and honest man. If what you do does not work he is strict but fair. But the best way to find out is to come and visit him, to experience him and see with your own heart and eyes. This is the best way to know someone isn’t it? True practice like everything in life, is about direct experience and to go and meet reality which is a reflection, an expression of the truth…you might like it or not, maybe someone prefers to just be a high rank and to have huge following or be famous, or whatever...everyone chooses according to his own appetite and what he looks for. But one should not forget that every choice includes consequences…and the street, the real fight, the life problems are here to test your practice which is an extension of the relationship with the master, the relationship with the art, and the practice of this art as well. Bujinkan appears as one lineage or branch of Ninjutsu — that of Masaaki Hatsumi. Is this the case, or are there are other schools that have come from his lineage…and if so, what are their differences? First it is important to be precise on the word you use. Please forgive me, but Bujinkan is not at all a lineage or a branch of Ninjutsu. It is just the name of an organization, the name of the dojo, many like it exist in Japan and have done so since the Edo period. Now for many people, it became a name of a strange style where everyone created his own way based on the very subjective word and state of mind called “feeling”. Honestly and sincerely speaking, I do not care for the organization and the way it goes as well, with all of the “childish politics”, “two faces”, “nonsense movement and impossible techniques” it uses as the main stream. My only concern stays with the nine-ryû ha, the master/disciple relationship and everything that goes with it: deep and wide knowledge, respect of each detail and technique without forgetting anyone or the history, the respect of the biomechanics as well as all the art and style, and of course the respect of the student’s body, mind and integrity. Now to answer to your questions, the nine Ryû -ha received by Hatsumi Sôke from Takamatsu Sôke, can be divided like this (some will say the opposite, but I can argue with anyone on that and I invite anyone to do so) 7 Ryû-ha received from Toda Sensei, 1 from Ishitani sensei (Kukishinden ryû) and 1 from Mizutani sensei (Takagi Yôshin ryû). The seven ryû-ha from Toda Sensei are the ones that are simply based on Ninjutsu practice, mind, strategy and combat. The one from Ishitani Sensei is also considered as Ninjutsu, because of the history of the Kuki family and his relationship with the Iga and Kôga area. Finally the last one from Mizutani Sensei is a Sôgô-bujutsu (総合武術) a composite system of combat that includes different disciplines based on the art of Jû-taijutsu. The founder of the Takagi Yôshin-ryû was a top student of the Takeuchi-ryû Koshi No Mawari, one of the very first ryû-ha of Jûjutsu in Japan which is a Sôgô-bujutsu that deals with the Bugei jûhappan (武芸十八般) or the 18 disciplines of combat that any Ryû-ha before Edo period used, taught and where all the past Sôke developed high level skills. But this is the history before Takamatsu sensei, according to the autobiography of Takamatsu Sensei, Meiji Moroku Otoko (only Hatsumi Soke has it, Takamatsu explained everything inside, his practice and relationship with the art, the difference between his masters, the way they taught him, his life in China etc.) we need to understand that Takamatsu sensei was deeply influenced by his grandfather (some say his uncle, but this is a misreading of the kanji used to write grandfather), Toda sensei who was from Iga and taught him the way to move as well as the science of combat of Ninjutsu. So before Takamatsu sensei started under Ishitani sensei and Mizutani, he was deeply influenced by the Ninjutsu form and spirit taught by Toda sensei, so it’s easy to understand that when he learned the techniques from the other two masters (Ishitani and Mizutani), he applied the main principle of Ninjutsu which is known as a Gokui called Suieishin (水影心), “the heart (mind) reflects the water or the shade of the water”, this is the capacity to copy any kind of technique, style, and make them better. It’s something that every high class bushi (warrior) or founder of Ryû-ha, no matter what the style, could do more or less, and in the case of Ninjutsu, this state was pushed to the extreme. This ability is also connected to the Musô tensei (無想転生), which is, only the one who will become the Sôke could do it. So for me, based on the writing of Takamatsu sensei, the nine ryû-ha are shaped in Ninjutsu’s mind and form. There is of course differences between the Ryû-ha, techniques, weapons etc. but the goal is the same, to kill and prevent danger and survive. Some are more direct, more pragmatic, some have more details, some less… you must study and practice all of them with no differences. By that I mean to practice, and study and work hard on the common points of each in order to make sense and measure the depth of the knowledge accumulated by each generation behind each technique. But to tell you the truth, it’s not the lineage or the difference that matters here. It is what you can do against anyone and how you can explain, present, prove to, no matter the master, the Shihan, the fighter or the style you have in the front you!! Most Japanese martial arts senior grades go up to either 10th Dan or 9th Dan, the latter being in recognition that one can never achieve the perfection and must always strive for the next level. Why are there so many Dan grades in the Bujinkan? And what is more important, Menkyo Kaiden or 15th Dan?Well, your question is in relation with the rank system and the way ranks are given in the Bujinkan more than anything else. I agree that this is an interesting topic among many, but as I previously pointed out I do not care for the organization, so I do not care about the rank system; First of all I must be honest about that, like I have been in front of many people, whether they are from the Bujinkan or other organizations, Ryû-ha, style etc. I have also presented this in Japan in many universities and in front of many high ranks of many styles: I do not believe in rank, the system of rank in classical martial arts and modern arts in general. Why? The reason is simple, in the history of any Ryû –ha before Edo period shows that ranks did not exist!! The only thing that existed was the Inka (印可), attestation of transmission, which means that the disciple who received it has been taught to a certain level, but it doesn’t mean necessarily that he understood it or that he could do it at the moment he received it!!! Phrases like “now you must practice even more” at the beginning of the attestation, and “disciples who study the art must always keep on practicing hard and deep” at the end of the attestation, is proof that it’s just the beginning! Because before Edo Period, the true rank was how many heads you took on the battle field? How many great warriors you fought and killed? What your behaviour and actions were during war and combat whilst fighting with the enemy etc. A man, a disciple was measured according to his actions, not according to the number of techniques and how much he paid for his rank. And, with time, the attestation or any kind of rank, paper and ink, could be bought, or sold. The need for money for living, providing for and supporting a family, created a need for people to reach a certain position or status etc. were good enough reasons for someone to run a dojo as a profession. And in the Meiji period, the attestation becomes a rank, Dan and Kyu system, with Jigoro Kano the founder of Jûdô. But in this case it’s based more on school education, like examinations in the university, it’s not on the long term but the short term. The rank you could have passed yesterday, the way you could do a technique yesterday or performed a week later, will be very different tomorrow. Maybe worse or better….who really knows….this is the reason I do not believe in rank, I believe in true and long term practice, action, deep knowledge….I think the way someone moves, acts, and behaves, deeply reflects the true value of his practice and the purpose of his practice as well….But if someone who pretends to be a high rank, who wants to be recognised and respected because of the paper he received, who is arrogant, hurts the student in order to show how great he is, behaves like a master, has no knowledge, and always refuses the direct confrontation, well this type of person is just a …….. It is not easy to measure someone…humbleness is very important in that case; and it is easy to see how ranks, prizes and reward are high and even more so the ego is huge, so is the arrogance … that’s how I feel. In Ninjutsu there is no rank, only action, application, skills…and please note that in “skills”, there is the word “kill”…I think that the nature of the word here, shows that everything should be a reflection or an expression of the reality, and everyone knows that reality is cruel, hard, direct and there is no compromise; Can you knock down your opponent or not? That is the question. Then the second question is can do you it with class and style and without bad intentions? So I do not believe in rank, but I understand the purpose, in a social way, in an education system or for sports according to its rules and scales. But the problem is that sooner or later there is a limit and the reality of the street and the true confrontation is always there to show and mark the difference with rank. “Rank is just paper, and its only good for the toilet”, Takamatsu Sensei used to say to Hatsumi Sensei… I deeply believe that to be true as well. Unfortunately, the world is made in such a way that the name, the university, the paper is more important, rather than the human, the one who should carry the rank… everyone should re-think that the name, fame, university’s name, rank, paper etc. cannot exist without the one who created it first….. That is man himself. Of course I respect hard work and dedication, even if it’s limited in a certain way, behind the rank. Someone who has worked hard for his black belt etc. the hard work in Judo, Karate, Kendo, and BJJ is really present and must be respected. Now it’s important to keep in mind that it reflects just a moment in life, not all of life, and not even the meaning of Shugyô or Keiko (used in classical Bujutsu and Ninjutsu. Those words include the aspects of the path and deep reflection of the past, of all of your life, so it is difficult to measure… Now in the case of the Bujinkan… well I do not care. Ranks are given for many reason: supporting the organization, by promoting and ranking other people, helping to organise Taikai etc. Do not forget practice as well, but what is the nature of this practice? Does the rank received in the Bujinkan really and deeply reflect the relationship with the art and the master or just the fact that you came to Japan and sacrificed your money for the promotion etc.? Honestly, like I said, the way people move, act, behave, sell themselves, promote themselves, the way they walk, is enough proof to show what they want and who they really are. In that case, I much prefer people from MMA, BJJ, Boxing, Muay Thai, Wrestling, Judo etc. because even if it is a sport and no one died/dies during the creation and application of their techniques, they are true in a certain way, their results and actions speak for themselves. They are dedicated and very tough and disciplined and it shows in their practice. But in the Bujinkan? Well I have no comment and I do not really care. The last thing I can say is this, as I have translated many times for Hatsumi sensei during class, like a few others who have lived in Japan for a long time (Mark Lithgow, Mark O’Brien, Andrew Young, Shawn Grey, Bruce, Doug, Larry, Paul, etc.) and who keep translating for him now, they have to hear the same phrase all the time: Hatsumi sensei said that the 15th Dan means that it’s the start for everyone. So it’s a direct reference to the historical aspect of Ujin, which was the age, 15 years old, of a young boy to go to war after he had passed certain tests. So the rank does not really express anything, only something to help, to push, to go more deeply, to keep on practicing. But we will be able to see the value of their rank after Hatsumi sensei stops teaching…here again the rank does not show the future, but just the moment when you received it… and everyone knows how humans can change, for the better or the worse. Now the high ranks in other organizations are also based on politics, actions done for the organisation, not just the skill anymore. For me the best rank is what you could do, when you are old and must face any style, if you can keep the flexibility required at the highest level and still practice. As a conclusion to this question, I do not care for, or of the rank, but the person. Rank means nothing to me. Perhaps because it was such a secretive discipline, there is often much doubt cast upon the validity of the remaining Ninjutsu systems and conjecture about their true origins. How many unbroken lineages of the ninja arts still exist today, to your knowledge, and what proof is there of this?Well, you need to understand that even the validity of the most famous Ryû-ha of Japan, is not really clear. If you want to believe that a Kami gave the art, or a Tengu, or that inspiration and teachings came from dream, and that allowed you to open a Ryû-ha and find inside it the highest subtle techniques etc. and if you present this in a front of academic, scholars, professor, you will not be respected. You need to explain all the mythology and the context as well, being aware of the history and the different influences. It is not that easy and its very complicated, because history is complicated, facts can help, but they must be able to be interpreted from a neutral base, and this, I am sorry to tell you, in the world of Bujutsu and Budô, nowadays the way the student believes blindly all the words from their master, who sometimes just repeats what they heard from their master with no historical proof or fact, it is really sad and will not change…it is like that. What you need to understand is, as long as there is someone who has the capacity to answer, physically and intellectually to any questions, someone who has the information and can demonstrate the application of the art with the highest level and most subtle skills, it is a proof of a certain continuity. I do not know how many unbroken lineages still exist today, there are a lot of scrolls and records that explain and present different information, some are interesting but do not deal with a certain Ryû-ha in particular. Some just mention a list of Ryû-ha or a name from a Ryû-ha with nothing further and sometimes it is enough to prove their existence etc. After that it depends of the practice, the way it is done, the movement, the form, the quality of the movement and the evolution of it…because Ryû mean flow, to keep on moving… it’s not fixed… so it’s not unbroken… if it is broken, the Ryû-ha will cease to function and will disappear. How far back can we trace the schools other than Kukishinden ryu and Takagi Yoshin ryu?This is very easy: first you need to know the history of Japan, the history of bushi (warrior), military history, and then the history of Bujutsu, Heihô. You must also study the history of all the various Ryû-ha, to understand the context and analyse the movement and the form of combat as well as the evolution of the weapon. To that you must add the etymology of the words, the study of the language and writing. Finally you must be very concerned with the human relationships in all the aspects of the transmission as well as in the master-disciple’s relationship. Once you are aware of all the various complicated and subtle details, and have not just done “research” e.g. copy and paste directly from Internet or Wikipedia, work which was translated by someone who does not have any background in Japanese studies at the PHD level in the field of bushi (warrior) history, or uses phrases and statements like “my teacher said to me…” or “I heard someone say…” etc. you can evaluate and measure how far back a ryû-ha goes and trace its movements. Now to answer to your question, after I have had the chance to have access to the densho written by Takamatsu Sensei, then analysing the history and techniques, the biomechanics and the form of each technique, the lexical analysis (relating to the words or vocabulary of a language) etc. I can easily state that most of them stretch back to the period Momoyama-Azuchi (1568-1603) at the end Sengoku Jidai (warring states period). Some of the techniques and words are from the end of the Muromachi period (1337 to 1573). But again, all of this means nothing if you cannot face anyone, from any style, technically (physically) and intellectually. Because after all what makes the flow is the capacity, faith, heart and intelligence of the one who dedicates and devotes his life and heart to it. Could you please describe what Kata and Waza are and the difference between the two?What you asked me will take too much time to answer, and I do not think that it is possible. Let me just give you an example of how deep the history of the kanji, or words, you ask for. What is the link between the tea ceremony, or Sadô, and the Japanese classical martial arts? What is the common point between the Ikebana (flower arrangement) and death by committing Seppuku (ritual suicide)? The Kata’s notion brings all the answers to all questions. In Japan the word Kata can be written with the two following ideograms (型) or (形). Both reflect various aspects, such as philosophy, technique, teaching, transmission, way and goal, all dedicated to the idea of perfection. Even if some claim that the Kata comes from a very long tradition, it was created mainly during the Edo period (1603-1867) and is still present in various fields nowadays. During the preceding centuries, many cultural elements were added to the Kata in order to create a structure where various specialisations of Japan found their base. You can translate the first one (型) by form, shape, and the second (形) the structure. Most of the primary records and sources that deal with Heihô, Bujutsu and Ryû-ha history and techniques, we do not find in them either of these two kanji. Which means that the primary way of using the body was something more difficult to describe by words, and was very difficult to show a form, even if it (using the body) started by using a form or a certain body structure. The main reason was that most of densho (transmission documents) never describe the most important things, because it was passed down through direct practice and direct transmission, not by words or writing. The best example of Kata is in Karaté, where you have just like in Chinese Wushu different forms that you can perform either solo or together. Now for Waza translated often as technique, you find two kanji (業) and (技). Both give the idea of technique, technical, like engineering, art-craft etc. But the first also includes the aspect of it not being easy or being difficult to grasp or reach. It is used also for the word Shugyô that can be written in two ways (修行) and (修業). The first one includes the reference of the way, path, effectuate, go etc., and comes from the esoteric Buddhism’s lexical. Both words include the meaning of path, hard and deep practice, never ending etc. In any discipline in japan, in order to explain something, a movement, a form, everything starts with a succession of form, a position connected between them by a link, the way you shift the weight of your body from one leg to the other for example. From this beginning, the essential aspect of “centre” or chûshin (中心) in Japanese appears clearly in the form. We can say that Kata include all the aspects that help to shape and build the structure that allows one to follow the image of the master, which shows the way to go, the goal to reach, the state of mind to cultivate, but the Kata is not stiff, not frozen, it is in motion, always in motion. The Waza or techniques are the application of the form, the actual use of the form. The Waza depends on the Kata’s quality, the quality of the internal structure (bones, inner muscles, spine, direction of the bones, the way you hold a weapon, the way you kick, strikes, use your fingers, grab and hold etc.), then the quality of the outside shape (perfect alignment, the right phase and the reflection of the master’s image, precision, sharpness, speed, balance, noble, direction and orientation, grace and beauty, and of course the expression of the heart’s state…in other words there are three very important aspects which are common to all the arts, sports, disciplines. In classical Bujutsu they are called the Maai (間合い), Hyôshi (拍子), Yomi (読み). The first one is often incorrectly translated as timing, a word that reduces too much all the aspects and dimensions concealed in the kanji Ma (間), found in various words in Japan like Kyakuma, Hiruma etc. Maai, represent the capacity to coordinate at the right point, according to the correct and perfect distance, timing, breathing, movement, delivered or exchanged between two opponents. It includes the measure of the distance, of calculating the angle and direction, space and distance, time and atmosphere of the moment, ground quality, heartbeat etc. and all of these should match at the right point with the correct synchronization. When you have this, you call this Maai. I forgot to add that in this case, it is not something you can do with a slave student or someone who falls over at any time, for no reason, like you find in the Bujinkan and many other styles, you must be able to do it and use it against anyone and practice hard to reach this point. This is Maai. It is more than just timing. Hyôshi (拍子), is the rhythm, the cadence, everything that deals with movement cadence and rhythm, the way you breathe, the way you move, the way you shift your weight of body, the way you will match it with your enemy’s movements etc. Finally, Yomi (読み), is the capacity to read the movement of someone, then read how he will move or use his technique. As you can see, Kata and Waza are deeply connected together. Of course you will read and hear people say things like have no form, no technique etc. but most of them “fight” or “dance” and play only with their own student-slave. I am talking here about historical and biomechanical aspects and dimensions that come from the reality of combat. In other words, technique and form, tactics, strategy and state of mind that are cultivated, polished and conditioned in order to prevent danger and annihilate it by any and all means necessary. Not to dance and use other fake mystical things used in order to cover the lack of knowledge, practice, experience and heart. To finish and in order to open a dimension that I hope will show you how the art of copying a master, a high class master, to practice true, is not easy and very deep, let me analyse for you the Kanji Waza, the one used today by most. This Kanji (技) is constituted by two Kanji: the first is (手) and the second (枝). The first one means the hand, the physical hand. The second one, means to support, the help, it’s also the part found in the Kanji for “branch” of a tree. A deep analysis based on the master disciple’s relationship, as well as the true experience of the practice and of human behaviour, allows one to interpret the Kanji Waza (技) as the hand that supports, the hand that helps. This can also be interpreted as, what supports the hand? What helps the hand? Helps and supports what? The art, the master, to support the duty, to help everyone… or the master to support and help the disciple, the stranger, the loser, no matter what….and for that you need a pure Waza, a pure Kata that reflect the purest intention. How are Kata different in Classical Ryu like Tenshinsho Katori Shinto-ryu or Kashima Shin-ryu or Shinkage-ryu, compared to the Kata in the 9 ryu that make up the Bujinkan?No the kata are not different at all, they share the same nature, the same goal, the only difference is the quality and the nature of the master, his purpose, the capacity to always be ready to face the changes required and to fit the time and the period where you live. So there is no difference. After that, it depends on the application and the vision of the reality you have; if you want to live in a period of weapons like katana, spears and other weapons that are anachronisms in real fighting or combat today, or use all the methods, strategies, tactics, body and mind knowledge, deep body biomechanics in order to respond and fit the reality and the time where you live today. Is the word and concept of Kata different in Gendai Martial arts (modern) then Classical Martial Arts?Like I said, the words or kata did not exist in primary Ryû-ha, the idea or the concept as you said, maybe, but in reality, I can say no. You must also keep in mind that what we call Gendai Budô, is made for sports education, competition, etc. and is very far away from an art of combat used for killing, to prevent danger, used during large scale combat or war, which was the purpose of all the classical Bujutsu and their respective Ryû-ha. This of course, depends on the history of each Ryû-ha, but mainly what we refer to as classical Bujutsu, Heihô it’s all about war, in other words, military, combat, spying, information, assassination etc. It is not for fun, or sport, to win medals or attain ranks, but to stay alive and protect your family, the lord, the clan, the country etc. you do not go to war with sports techniques, you do not face terrorists or any kind of threat with sports techniques, no matter whether they keep you in shape or not! It is important to be pragmatic and realistic, or at least to have a bit of honesty. Because the technical aspects and the mindset as well as the goal is different between Gendai Budô and classical Bujutsu, it is logical that even if they share common ground based on the use of the body, their purpose and intention is different. A popular belief in Japanese Martial Arts today is "No left hand". So we see lots of Japanese weapons based arts teaching sword work for example with only the right side being practiced. You on the other hand put great emphasis on being ambidextrous with all weapons and body movements. Is practicing both sides common in Classical martial Arts or just in the 9 ryu of the Bujinkan?It’s important here again to be a little bit honest and realistic. On the battlefield, during combat, during the chaos you use any weapon or anything you can grasp or hold onto as a weapon. It is logical that you will use your both of your hands and both legs. Do you run just with the right leg when you must escape? Do you climb with just with your right arm when you need to evade? Does a boxer fight only from the right arm? Of course not, you need everything in case of an imminent threat or danger. There is no proof that masters of the past, professional killers and warriors used only the right arm or hand, and this will be not logical in the case of deadly fighting. It is logical in true combat and war to use, to condition, to polish skills from and with both hands. Because what if your right hand is wounded, what do you do? Would you stop the fight? Seriously? Same as with weapons, you must be able to use both sides in the same way, to the same level of perfection, this is the perfect balance and this is also connected deeply with neuroscience, the body and mind’s health…in my case I always practice both sides and all the densho written by Takamatsu Sensei on the techniques of the nine Ryû-ha mention after each technique to practice and apply them from both sides the same way. I also suggest to everyone to always practice their weakest part, which can be in many cases the left side if you are a right handed. But everyone is free to do as he wants. What is the difference between To and Ken, and then Tojutsu and Kenjutsu?I have already explained this in various seminars and conferences as well as in my thesis. Tô (刀) refers to the Sabre, in can be read as katana, there exist many different kinds of katana, lengths, shape etc. The first Nihon-Tô (日本刀) or Japanese Sabre, was created in Kamakura period. Before that what was used was the Ken or Tsurugi (剣) the straight sword which was influenced by weapons from China. Until the end of Edo period, most Ryû-ha never used the word for Kenjutsu, but mainly Tohô (刀法methods of using the katana whatever the length or the shape) or Tôjutsu (刀術) techniques and direct applications of the Sabre methods). The use of the word Kenjutsu, like in Kendo at the end of Edo period was more as symbol. In most of the scrolls, in order to legitimise the use of the weapon, especially the Sabre, during a period where the use of the weapon was severely governed by the Tokugawa government as well as the warriors behaviour and actions, it was said that the science of Heihô and Tôjutsu was a gift from the Kami (spirit) of Japan who used a straight tree branch or perhaps some type straight sword. The influence of the mythology of Japan, in books like Kojiki, where it explains the history of the foundation of Japan by Kami and their actions it is really important to study here and see how many bushi used it in order to legitimise their practice and actions or to give a symbol, a noble purpose to their art and action, a throwback to times gone by. It’s also a way to try to show the difference with more violent way of using and teaching the art of weapons. In conclusion the use of Kenjutsu, techniques of the Tsurugi- the straight blade, came as a logical answer to the time and place of the period where bushi wanted to give a new orientation to their art and practice. But if you observe deeply, you will see that all the people who use the word Kenjutsu, in fact, in reality, the weapon they actually use is still a katana, a sabre and not a straight blade Tsurugi like in Chinese Bujutsu or European fencing. I could of course explain more in detail and argue the point with scrolls, records and examples, but I think it’s enough for everyone who will read this article; like for everything I said until now, I am always open to answer directly to anyone who will ask me directly, not by the internet, but face to face. In Australia there are still Bujinkan schools teaching things like the Godai during class in relation to feelings during techniques they teach. For example Fu (wind Technique) being light and circular or Ka (fire) being aggressive or Chi (earth) holding your ground against the enemy. This has nothing to do with teachings from Hatsumi Soke does it? These are ideas brought in by foreign students to basically sound more mysterious and interesting? The truth is the Godai are found in other parts of Japanese culture and are used as a method of counting?Well what you just said about the Godai, or Gogyô Inyô no Setsu for the full word, is true. It is a science that came from China. It is connected with the practice called Onmyô-dô that deals with divination, geomancy, calculating, ready the sky etc. There is a lot research done in this field in Japan and many other universities all the around the world who have a Japanese studies department that is advanced enough to research it. The level required to study this field is quite high. You must know Kanbun (Chinese writing), be able to read and write it, as well as know other aspects of the Japanese culture, civilization, history and language. Now about your question, let me be clear, the nine Ryû-ha from Takamatsu sensei, passed down to Hatsumi sensei do not deal with this at all!!! Even Hatsumi sensei does not talk too much about this, because it doesn’t help you to be more accurate, more precise, sharper or more effective. It only helps you to lie, to cover the lack of knowledge, to attract the students who look for weird mystical experiences and to overpower the ignorant! These ideas started with books written by Stephen K. Hayes and everyone copied him. This is connected to what I said before, the capacity to copy, leads to the Art of Copy, you must have the right to copy and to copy right (the right master, the right model, the right example), otherwise, excuse me for being rude, if you copy shit, you reproduce shit and then what happens, you end up in the shit so deep that you cannot even get out of it, the truth it hurts…but the truth is this, like attracts like, so shit attracts shit , it seems this is how it has gone since the beginning of human kind. I do not know why people use it, but honestly the use of the Godai or Gogyô its more to separate or classify things, like chapters in a book for example, just like the idea of Tenchijin (heaven, earth and man) that everyone takes as a bible, but was just used to classify and catalogue a list of different things in one book; what is more funny and sad is that all the people who use those concepts (which they do not understand at all), when you look at the way they move or apply any technique or use any weapon etc. they do not move like the wind! (Fu) They have no class, no style, nothing, in their classes or seminars they spend more time talking and brainwashing people than practicing, they never sweat!! Only the blind and the people attracted to what is not effective, not logical, are involved in this. Keep in mind that at the origin of any kind of Ryû-ha that when you start talking about the use of the Godai or similar things, that you have professional killers and warriors who did not care about the Godai and other things like that. Why? Because it doesn’t help you to survive in battle, let alone to go out and face a professional MMA or Muay Thai Fighter!! Please be serious, open your mind, only the right and correct practice can help you. You know I like Star wars, Marvel, and other things like that, Manga, movies, but I know the difference between reality and fiction, and reality it hurts! Just like stupidity does too. What are the main differences in learning and studying the nine Ryu of the Bujinkan, compared to other Koryu in Japan?There is no difference, what will change is the ambiance, the dress, the code, more etiquette or less. But the essence always stays the same. Then everything will depend on the character, the nature and knowledge of the master who teaches and the disciple who receives. But there is no difference. Here it is important to explain first what a Koryû is. The main translation known and used for Koryû (古流) by a lot of martial arts’ lovers and adepts, whatever the school or the style, is “old school”, or “traditional school”, “classical school”, etc. in the origin of the Koryû there is a master-founder, mainly a warrior or bushi, who after deep practice and various battlefield experiences, he finds a deep subtlety of using the body and the weapon (in other words, to kill faster so he can stay alive). During the Meiji period, those master-founder’s will come to be called Sôke or Iemoto (家元). In Koryû the masters use different modes of transmission such as Shinden, Taiden, Kuden, as well as different writing calls Mokuroku, Densho, Shuki, Hiden-sho, Kuden-sho, Hibun-sho (or Himon-sho), etc. In order that the master accepts a disciple (who is also a warrior) (there are also fee’s and gifts from the disciple attested by various records), the disciple must have a recommendation letter (suisen-jô) from well-known warriors or from the warriors of the same sphere as the master, and write an oath call the Kissho-mon, where the disciple swears to never betray the master or the secrets of the Ryû. After a certain time and practice, trust is established and the disciple receives an attestation of transmission called the Inka-jô which originally came from esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyô)’s transmission mode call Injin Koka no ryaku. The Inka-jô was use in the Zen’s transmission. Most of the sources show that according to the nature of the relationship between the master and the disciple, the content of the Inka-jô, as well as the techniques transmitted, change. According to the period, the position of the master in the warrior class, his name, his skill, his motivation, there are also many cases where the Inka-jô was sold. This presentation gives the general idea of what is a Koryû. But to be honest, I don’t really think that the translation “Classical school” or “Old school” really covers the deep meaning and all the different aspects (historical, philosophical, practical, ideological, sociological, as well as the human side) included in the word Koryû. In Japan, in both the scholarly and martial arts world, most of the people, masters (sometimes very high ranking instructors, Sôke, Menkyo Kaiden (免許皆伝 Full Transmission) holders, practitioners, scholars, etc. often confuse the actual facts with their own views, wishes, their own practice and experience, and cannot really give a clear answer, as well as explain this word exactly. Even if there are many factors in this confusion, it is very important to know that there are different types of Koryû. According to different studies and researches on various scrolls and chronicles, it’s easy to see that there are various Koryû created in different periods of Japan’s history. Some were created before, during and after Sengoku Jidai (warring states period circa 1467-1603); others were created during the three parts of Edo period (1603-1867 Zenki, Kôki and Bakumatsu) and finally, a scholar must also consider the different Koryû created during the beginning of Meiji restoration period (1868-1912). Because of all those aspects I personally think that translating Koryû literally as “old or classical school” is not enough when someone makes claims about himself being a scholar or a serious researcher in that field of study. I can also say that whichever Koryû someone practices, he should be aware of the historical context, the reason for its creation, the different changes it underwent for various reasons (technical, theoretical, ideological). Not being aware of all those aspects is, in my personal point of view, a kind of blaspheme or disrespectful attitude, as well as a sign of ignorance towards the art and the various generations who created each technique. But let us come back to the topic of Koryû and try to explain or give a different point of view. The word, Koryû (古流) is made of two kanji: 古 (ko) and 流 (ryû). Anyone can take a Japanese dictionary or a kanji dictionary and see that the first kanji (can be read also: furui) meaning: old, out of date, old fashioned, outdated, archaic etc. same for the second one (can be read also: nagare, nagareru, nagasu, nagashi) meaning: flow, run, rush, shed, flush, current, stream etc. It is very interesting to notice, even eloquent, that the second kanji does not mean or refer to at all, the English word “School”, or even in French, “Ecole”. In Japan the word used for school is Gakkô (学校), and the first mention we have about the use of the word Gakkô (学校), stretches back to the Ashikaga family, a famous family of Shôgun from the Kamakura and Muromachi’s periods. There are many theories about the creation of this school, the two mains theories are, it was created by Ono no Tamura during the Heian period (11 century) or created by Ashikaga Yoshikane during the Kamakura Period (12th-14th century). This school is considered as the oldest in Japan, and is located in Ashikaga city, Tochigi prefecture. It was established to educate members of Shogun’s family. High class monks use to teach mainly Confucius studies and Yi-Jin science, but military science and medicine were also taught etc. You do not need to be a PHD in Japanese studies, to see that there a huge difference between the Kanji Ryû (流) of Koryû and (学校) of Gakkô! So in Japan, the historical chronicles and diary’s mention the word school, Gakkô (学校), which refers to an established place and was used for young boys from high class warrior families to come and learn different disciplines (nothing connecting to Koryû) under professors (mainly monks), it’s easy to understand that there is a difference between Gakkô and the Koryû. I think that we can easily advance to the idea that Koryû does not mean “old or classical school”, because in the history of the first Koryû of Japan, there is no indication of such a centre or place established, with the name of Ryû outside the house or dôjô, administration, various teachers, fees, etc. We must wait until the Edo period and especially to the midway point of the second half of Edo period in order to see warriors settling down with places such as dôjô dedicated to the teaching of different types of Koryû. It is important to search where the first mention of the word Koryû came from, in order to have an idea of what it means and how it has change, it’s the same for words like Heihô, Heigaku, Budô, Bujutsu, etc. Since Meiji until the present day, in most the cases, the use of the Word Koryû is use to mark the difference with the Gendai Budô (Modern Budo-Jûdô, Aikidô, Kendô, Karate- whichever the different ryû of Karate etc.) created since the Meiji period. Moreover, the first mention of the word Koryû can be found in different scrolls like in the Kage-mokuroku (影目録), written in 1566 by Kamiizumi Ise No Kami (1508-1582), founder of the Shinkage-ryû (新影流), as well in one of the oldest densho on Heihô or Hyôhô (兵法 Strategy) written during the Muromachi period, the Kinetsu-shû (訓閲集). In both, we can find the following words, Jôko-ryû (上古流) and Chûko-ryû (中古流). Those words are also used by Kamiizumi Ise No Kami in all his writings. Those two words refers to two kinds of Ryû: the Jôko-ryû represents the primary Ryû of Japan, from the end of Heian period to Kamakura period. And Chûko-ryû represent the Ryû from the Muromachi period like Nen-ryû, Katori Shintô ryû, Kashima Shintô ryû, Kashima Shinkage-ryû, Kage-ryû, Chûjô-ryû, Shôsho-ryû, and certain Ninjutsu ryû etc. Accordingly the explanation we find in those two scrolls, we can say that Koryû cannot be expressed by the word “School”, but more by the word “”circle” (like a private sphere of transmission and practice), “a private flow of tactics, strategies and combat”, “way or vision of life based on battle field and combat experience”, “current of thought and use of the body” etc. This indescribable flow of using all kinds of weapons and to be able to apply any kind of technique to kill and survive, was created by professional warriors (killers, assassin, survivors etc.) who, for various reasons, dedicated their lives to the Art of Combat. In order to have access to those warriors, to meet with them, to receive their knowledge, most of the records show that they did not have any place known to be like a fixed “School” where they taught and received money. So in order to meet with them, one must be introduced by someone, mainly a warrior (Bushi) who has the right connections and relationships, a kind of warrior only network, exclusive to the art of Heihô (using weapon and body technic on battle filed, leading troops on the field, strategies, tactic, spying, etc.). To be introduced, you must have deep connections, and in order to have those connections, you must have a special position in the Bushi (Warrior) class. It’s important to know that, the one who had access to those masters, professional killers and warriors, was already a warrior himself, which meant they already had fighting and battlefield experience. For certain reasons most of those masters did not accept service to any kind of Lord or Daimyô. (Certain chronicles and records do mention that certain masters did accept to transmit or present their techniques to a few Shogun, Daimyô and Kuge). They were free, their way of practice was free, so they could not have any fixed or established place, because in the art of war, it’s important to never fix things in place, and this aspect is directly connected with the Kanji Ryû, the flow, the art, the technique must never stop, it always adapts itself to the situation and period where the master lives. This is natural, because the vision and the art they cultivated and practiced deeply was done everywhere, at any time, in daily life. Also it’s really important to know that they did not have any kind of methodology of teaching, transmission etc. they just shared it, because it’s very difficult to cut the flow…very difficult… As you can see, historically the first Ryû did not have a place known in a fixed location of course there are famous temples, sanctuaries where the founders may have learned some things, but nothing specific. Heihô, Bujutsu, were not taught in a public way. It was always private, deeply private. From that context it is very clear to understand the importance of different transmission modes such as Ishin den shin, jitsuden, jikiden, naiden, gaiden, shitsuden, etc. One important aspect to not forget at all about the word Koryû is that it will evolve and follow the needs of time and history. When dôjô started to be established, the transmissions opened to the public, this created different levels, methodologies of teaching, selling ranks and Menkyo (licences) as well as scrolls, technical developments, weapon and tool evolution during practice, etc…the flow of the art will change in order to satisfied the demand and needs of the period…Sometimes the flow will stop or crystalize itself…so it must wait for a new generations Soke or Iemoto, who can connect the bridge between two periods and explain what previous people or current students could not express or understand. But the main and crucial point is to always keep in mind that this is in a warrior’s sphere of influence, a Bushi’s world, where the only question is “who can stand at the end of the combat?”, “who has the capacity to fight, and to apply the technique and adapt it against any kind of style, man and technique, whatever the situation and the context?”. By presenting all of those explanations, someone might think I did not answer the question directly “what is a Koryû?” First of all, I think it’s really important to give a large vision, some historical aspects about Koryû. The word Koryû cannot be just translated as “classical or old school” where, nowadays, one master who never challenges himself and presents himself like an old traditional guy that follows the real samurai spirit, who brainwashes his student with movement and techniques that do not work at all. Whose goal is mainly for money and self-promotion. Most of the time someone who practices deeply his art (Koryû, Gendai Budô, whatever the art or the discipline), he always looks through his master’s eyes. If the master has a very stiff, limited, fixed vision and looks down on other arts as shit or if he underestimates others, well, you can be sure that the student will recreate this attitude as well, and perhaps even go deeper into this limited vision… such is life. As a conclusion, what I can say about Koryû is, the following two ideas represent what we can find today in Japan among most of the masters: “Classical or old school that teaches an old way of using the body and weapons according to a certain historical context and or a famous warrior’s knowledge. This knowledge or technique can become fixed and stiff with the time and completely not adapted for the real/present world and time anymore, but is still interesting for various reasons. In many cases the body motion and the techniques are not good for the body’s health and do not respect natural healthy biomechanics.” And “Classical or old way of using the body and weapons that shows a very deep flow in order to evolve and understand the human body and psyche through the experiences of various warriors (famous or not). Those experiences allow one to keep an open heart and mind in order to always keep the flow running, so you can face any kind of situation, weapon, man, fighter, warrior, killers, style.” Finally, for me, not being able to face any kind of style, man, weapon, situation at any time etc. with the techniques and knowledge based on the flow (The basic techniques of the Koryû you study), is not a direct representation of what Koryû means and also not what the founder of the Koryû had in mind when he founded the subtle techniques and way of moving at the time of origin and creation of his Koryû. In this way, Koryû becomes an old style, stiff, fixed, unrealistic. So it’s not really good for the body’s health in a certain way. But like everything in life, everyone chooses what he wants, but one should never forget the consequences... How effective are Koryu (Japanese martial arts, the Bujinkan, or Ninjutsu) today, in comparison with MMA and other sports martial arts?Here again it depends on the one who practices, how he practices, what does he practice, and what is the nature of the techniques he practices. From whom did he learn, what is the nature of the relationship he has with the master, the art, the practice itself? Etc. In essence, Koryû techniques are made for killing, for survival, this conclusion is logical. But the capacity to adapt to show a deep level and scary effectiveness with a great sense of control of emotions towards pain, to be able to take and endure it, rather than get hurt, to understand deeply and to demonstrate the difference between speed and flow, effectiveness and precision, with that of violence and stupid strength. To be able to stay open, flexible and be ready to face anyone are the capacities needed. I also think that the highest level of effectiveness is to be able to make someone from a background of say, a high level of MMA etc. realise, feel and sense without hurting him, using violence or humiliating him in any way, the difference. Honestly I think it’s possible and this is what I aim for. I like MMA, just as much as all the other arts, whatever the style or the country. I respect hard work and logical strength, I like craziness too. Ninjutsu is the art to be able to face everything, everyone, no matter what, but for that you must practice and study more and more, more and more, and never stop in the “more” aspect the practice….there is always a higher level, always deeper meanings.. It is never ending. The effectiveness depends of the human, of his heart, of his knowledge, of his practice. Not about his rank or Godai, or his big talk on Internet… How important is armed combat in the study of the nine ryu of the Bujinkan? Many see training with swords and spears etc. as antiquated in today’s world.Well, it’s true that nearly all the weapons are now completely anachronistic and useless. This is what most people might think, even scholars. And if you look how the majority of the people in the Bujinkan use weapons, it is blasphemy, especially when used in the front of other Ryû-ha’s disciples. The use of the weapon reflects your body’s ability and your mind as well as your capacity to measure and apply the three dimensions of classical Bujutsu I mention earlier: Maai, Hyôshi and Yomi. But it’s important to look at this according to a practical experience point of view. The use of the weapon as well as the weapon itself, teaches you the correct form, the right distance and measure, the right angle, the control, the accuracy and precision etc. because the use of weapon came directly from battlefield experience, where every movement cannot allow you to move the way you want or to act stupidly. In this case, it is easy to understand that one wrong movement, a wrong step, a wrong angle or incorrect form causes you to die or at the very least lose a part of your body. If someone practices very deeply and correctly with weapons, from both sides of course (right and left in the same way in order to cultivate the correct balance requested in all the Koryû), without weapons he will know all the right angles, weak points, timing, distance, space etc... He will be able to move as sharp as a weapon. All those movements and techniques will be deadly, precise and accurate. By learning the use of the weapon we learn to become one with the weapon, in other words we can materialize one of the Gokui (secret teachings) we find in different scrolls of Koryû “The form follows the function.” In this way the body, the movement, becomes a weapon. This allows one to find one of the highest levels in Koryû, which is the economy of movement and not use of excessive physical strength. It’s not easy, but this is the process concealed in the history of various masters and founders of Koryû (according to historical sources, most of the founders were known on the battlefield for their skills with long weapons and the number of heads they had cut off and present). They started with long weapons, because on the battlefield, bow and arrow (are used from a long distance), polearms such as naginata, yari and nodachi (great or field swords) are very long weapons and are more accurate to kill the enemy and protect the body. But once the distance or the long weapon is broken by the enemy’s weapon, in this situation you must be able to adapt and use what we have left around the belt, or in the hand or what is found on the field. From that experience, the disciple learns how to use any long weapons according to different situations that include various factors, and if he loses the long weapon, he must be able to adapt and use shorter weapons such as katana and other short blades or just their own body. After all, the hand and the body are the engine that drive the tools and weapon, if the body is well forged and cultivated, it must be able to face anyone or any style, with or without a weapon with no difference between them. A lot of people always say “the weapon is the extension of the arm” but who can really show it, apply it correctly and effectively? Very few… Actually the art of weapon should be done, step by step, centimetre by centimetre, millimetre by millimetre, in order to grasp every subtle detail, each aspect of the distance, the space between the weapon and the target aimed, the different timings, the different rhythms, the different breathing patterns, and the capacity to read the movement and measure all of the aspects of combat. With deep and correct practice based on the flow and the image of the master, step by step the distance and everything becomes shorter and shorter, in order to become very close to the enemy in order to kill or control him. Here again we can see the materialisation of the Gokui, “the Form follows the Function”. It’s not easy to reach this high level way of using the body, like it’s not easy to reach the level where it’s possible to move like a living blade through the art of weapon. But the arts of Bujutsu, Heihô from the Koryû are not easy, because it’s made of the life, blood, sweat and tears and the sacrifice of many masters. Yes, it’s not really easy, because you must be able to see and realise deep inside the body the common points between the use the body and different weapons, to finally be able to face any kind of style and man. I am really sorry if my answer is too long. Be aware that it’s possible to explain more and present more historical fact and example about this topic. How can one claim to study and hope to master nine different ryu at the same time?Hope is free and open to everyone, it can help you and push you forward. But hope without capacity, skills, strong faith and intelligence, heart and benevolence, and especially the right and correct example from master e.g. the form, orientation and direction, honestly, it is impossible. What you need to know is that the nine Ryû-ha are not different, they have the same goal or direction, plus they were taught by one master, Takamatsu Sensei, so he also taught to Hatsumi Sensei how to perceive the common point, the common link, the common essence between what looks to be very different from an outsiders point of view. It’s like the 5 fingers of the hand, they do not have the same length, the same use, some are stronger than others, and we do not use them in an equal ways, isn’t that true? But in order to grab or hold something, to help someone, to shake their hand, they’ll join all together and become one. Rather than just seeing the fingers, we must look at the part of the hand from the wrist as a whole…Here what I want to say is that everything comes from one unique movement, that allows you to copy and do everything. So in this case it is possible, but the work, the practice, the studies, the humbleness, the constant questioning, is endless… What place does solo training have in the Bujinkan?Like I said at the beginning of this interview, I separate the organization (Bujinkan) from the art (nine Ryû-ha). So really I do not know what it means- the place of solo practice in the Bujinkan! Because you just need to look at YouTube and you will see it is really….. I’ll let you decide. Practice means results, look at MMA, Muay Thai, Boxing, Judo, Karate, BJJ and such, there is sparring, its fast and furious, so there is something there. You can say that solo practice is very important. But in the Bujinkan, honestly I do not know and I really do not care. I do not live by, for and with the Bujinkan, I hope I am clear enough here. I live in Japan and I see and observe the “high class” Shihan, 15th Dan, whatever, coming from all over the world and practicing their way and vision, as well as the Japanese too. So really, I prefer to only look at Hatsumi Soke, and there I see what a true reflection of what solo practice is and how it is endless… For me the examples to follow are Takamatsu Sôke, Hatsumi Sôke and Ishizuka Shihan. They are the example that will push me to have no limit, to not reach a roof or ceiling, but to keep on going forever, to push forever and ever. I reject at the same time anything that can corrupt me or pull me down. It’s an ethic I cultivate. Now to answer your question more precisely, yes solo practice is crucial, it is the only way, the only key, the true results and practice are discovered here. This is my point of view, In Japanese there are a few words to express the idea, the action of “Practice” such as Shugyô (修行), Keiko (稽古), Tanren (鍛錬), Renshû (練習), Gakushû (学習), Narau (習う) etc. The most famous one includes all the aspects of the Flow (which are to practice deeply, study, research, experiment, application, act, repeat, copy, polish, reinforce, conditioning, etc.) which is Shugyô (修行). With the second kanji (行) this refers to the way, the path, follow the path (the question will be what or who to follow?), the way where you accumulate various experiences. This word comes from the spirituality of Japan and is very old. I honestly think this is really difficult and an incomplete way to translate Shugyô by “practice”, “exercise”, “training” etc. Actually it is too limited to only use those translations. But like in everything, it depends here again on what you have in your mind and how deep do you consider your practice. In order to consider oneself as a Shugyô-sha, it’s not about going to the dôjô for practice, doing seminars, selling a few DVD’s, ranking people, promoting oneself…its beyond that, those aspects I just mentioned are considered a good test to see if the one who has claimed to be devoted to the Shugyô did not corrupt his heart… The Idea behind the word Shugyô, it’s close to the way hermits, saints, religious men, devout men, monks, ascetics etc. practice and apply their faith and pray. Every day, every minute, every action, talk, silence, breathe etc. are devoted to their God, Buddha, whatever they believe. So for the founder of Koryû, a master or Sôke, this is the way they live their art every day, because in the Kanji Gyô (行), which can be read Iku or Yuku (even Okonau), there is also the idea of Flow, something we must walk with and become one with. Other words included with Shugyô and crucial to every person who practices Koryû, is the word Keiko (稽古). Here again these two Kanji do not express the action of practice. Many scrolls use this word, but the one who uses it in a broad meaning is the scroll from the Kitô-ryû jûjutsu. these two kanji can be read as “Inishie Wo Kangaeru”, which can be translated as “thinking about the past”, “reflecting about/on the past”, “meditating on the past, or history”, “Pondering about the history, the past”. In other words, this means that the disciple must, think, search, research how the master, founder of the Koryû in the past use to practice, use their body, the different reasons behind it, the concealed factors hidden behind each technique, movement and Kanji of the scrolls. What I wanted to present here is that the common aspect of the word “practice”, is really more than just going to the dôjô, following a logical order of repeating over and over, the techniques or movements without having and knowing why the deep purpose or high spiritual attitude behind it. If you consider that most of the people in the Koryû world as well as in the Bujinkan looks at what he wants and see the way he wants and practices what he wants, then what can we say about the meaning of words like Shugyô and Keiko? Like everything in life, there are degrees, levels. If someone is looking for the highest and deepest level of nine Ryû-ha’s science and knowledge, if he wants to have a subtle movement and understanding of the deepest aspect of the art and become one with his Master and the Flow, well the contract is simple, he must be ready to offer more than what is expected and more than what he thinks is deserved. And the more interesting thing is, is that there is no guarantee that you will be chosen or that you will even reach the highest level of the art. But at least, I honestly think that you will learn something incredible and priceless, the meaning of Patience and Humbleness, as well as the true Value of the Art, and this is already “Gold” by itself. Do you have anything you would like to say or add to the interview?Yes, first of all I want to thank you for giving me the opportunity to visit Australia for the first time. To answer your questions, you must understand that everything that deals with Ninjutsu can be very difficult to understand, or not seen correctly or with much respect. As a researcher and scholar myself I understand this very well, and the main reason comes from a lack of knowledge and study, in aspects of the art, the practice and the intellectual side too. Of course there is also all of the people who claim to be personal students, show and collect rank, take lots of pictures with Hatsumi Sensei etc. claim to be the One or to understand etc. then there is all of the jealous people, who are not recognised, who betray etc. who want to badmouth Hatsumi Sensei and Takamatsu sensei. I also understand that. But the most important thing is to meet and talk with them, to share experiences with them, because all of Bujutsu is about that, to meet reality. Same goes for Ishizuka Shihan or myself, please experience what we have to offer first hand and do not rely on the thoughts and opinions of others. If you are an adult, you should make up your own mind and not be a slave to the opinions of others.

I want to apologize if my words have hurt anyone, I am very up front and direct, but I never try to hurt or humiliate anyone. Now if anyone has something to say about me, who wants to try me, I am open and I always say it and accept it. I will come back to Australia even though some tried to use the Immigration office in order to stop me from passing Immigration and enter into the country, I did not come to Australia, just like all of the countries where I have been invited, to take a job, a place, the dojo or the student of anyone, or to make any money (I do not get paid for being here), I only come to holiday and practice with my friends. I do not need to be doing any of those things. I am a Professor and Researcher at a prestigious University in Japan. And I have no interest in doing anything like that. But how are people supposed to know it, if you do not meet and talk with me and see me for how I am in person, face to face, man to man? Also if anyone have something to say, well come and say it in the front of me. This is a mark of respect. And respect leads to the most honourable way. Martial arts and life starts with that, Respect and Honour. -Kacem Zoughari

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Seichusen BlogWelcome to the Seichusen Dojo blog where you can stay up to date with all of the Bujinkan Seichusen Dojo news and activities in Brisbane Australia Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed